Questions: Erica Grant, University of Glasgow

Answers: David Kamp, Studiokamp

What are some of the key challenges to designing sounds for a space? How have you overcome these challenges?

The primary and most obvious challenge is finding or designing the content, meaning the specific sounds that constitute the exhibition soundscape. What specific sound elements is the exhibition soundscape composed of? How close are these sound elements thematically/physically connected to the other exhibits on display? Is there a direct thematic connection between the soundscape and the exhibited objects, or is their relationship more abstract and disconnected in time or space? What does the soundscape add to the exhibition? Is the intention to add emotion and excitement, transport them to a specific place or time (by using field recordings, for example). Why use sound at all? Is there a need to have a soundscape for all exhibition areas, or should parts of the exhibition remain quiet? The answers to these questions are different for every exhibition and worth thinking about in the early stages of a museum soundscape production.

A more technical aspect to deal with is the acoustic properties of the space. Exhibition rooms are often large with many reflective surfaces, which means excessive reverb can be an issue. Most exhibition rooms are not planned or constructed with optimal sound/acoustics in mind.

Therefore it is beneficial to get the designers of the soundscape involved early, ideally once the exhibition design and concept start taking shape. Small changes to architecture and interior design, like slightly modifying drywall positions to avoid parallel walls, or using different surface materials in the exhibition room, can help to create a much better sound experience in any given exhibition room. For example, a sitting area with upholstered furniture in the center of the room can help improve a room’s acoustics by adding absorption – but only if the furniture’s surface material is acoustically transparent (e.g., a cotton fabric). If those same blocks have a leather or plastic shell around them, they would lose any positive effect on the room’s acoustics.

Suppose the room design is already completed, and the acoustics are an issue. In that case, we could capture an IR (Impulse response) of the exhibition room, measuring its acoustic properties. We could then use this “acoustic fingerprint” as a guide for our mix of the soundscape. This approach allows us to create a well-balanced soundscape even in less than ideal playback situations.

Unwanted “sound spill” between rooms or adjacent areas can be a problem, particularly when the audible sounds are not meant to be heard by the visitor at its current listening position. In such cases, the traditional solution is to use heavy acoustic curtains to separate different sound sources/rooms/areas from each other. However, curtains should be a last resort since they present a barrier of entry for visitors, which can cause confusion and disrupt the visitor’s experience.

These issues can be avoided at the source by designing the soundscape thoughtfully with the room plan in mind and planning in advance what content is audible in each area, and when. By using our custom 3D-audio playback solutions and working with the right type and number of loudspeakers, (some optimized explicitly for reverberant rooms), we can play some sounds only in specific areas of the exhibition, while others are audible in the entire space.

Are these challenges the same for indoor and outdoor spaces?

Outdoor spaces can have challenging acoustics too, but usually, the biggest issue is not the space itself. The potential problem is that there is much less control over the soundscape. Depending on the location, one might have to deal with entirely unrelated environmental sounds, like air traffic, weather, birds and insects, and all sorts of human activity.

If the location choice is flexible, the location with the least amount of environmental sound should be chosen if a “designed” soundscape is planned, and headphone use is not favored.

However, instead of fighting the environmental sounds, we might as well embrace them and creatively design with and around the existing soundscape. After all, environmental sounds are a big part of a place’s character, and sometimes they are what makes a place unique and exciting. A good example of this approach in my work is the soundscape concept I developed for the entrance area of the MAAT Museum in Lisbon. The omnipresent sound at the entrance is the massive Ponte 25 de Abril‘s traffic hum, which is about 1 KM away from the building. I made sound recordings of the bridge from various distances and different perspectives. In the studio, I amplified the bridge’s inherent resonances in those recordings, “magnifying” them until they could be clearly perceived, which gave them a musical/tonal quality.

I then took these elements and created a composition from the sounds. This concept allowed listeners standing on the stairs of the MAAT to experience the “live” sounds of the bridge, augmented every now then by my processed bridge recordings, which were played through the eight installed loudspeakers.

How does sound enhance interpretation of museum exhibits?

I think sound can profoundly enhance an exhibition if it is used well.

The default use of sound in museums is the audio guide, but I think sound can often add a new dimension to an exhibition that goes beyond conveying information. Sound can help structure an exhibition in a very subtle way and add a layer of meaning that can be literal or abstract.

To give a concrete example, I was involved in the early planning stages of an exhibition about Joan Mitchell at the Baltimore Museum of Art, curated by Kathy Siegel (BMA) and Sarah Roberts (SFMOMA). The abstract works of Mitchell were directly inspired by the soundscape surrounding her; from specific music pieces that inspired specific paintings to the rural environmental sound of southern France that surrounded her during her working period there. Creating a sound environment around these sound elements in parts of the exhibition was an idea I really liked.

What are some of the reasons that sound is often neglected in museums? How can we more effectively promote its use?

A recurring fear with curators seems to be that sound could be overwhelming or distract the audience from the other exhibited media (objects, images, texts). I think that ruling out sound means giving up on an entire layer of perception that can add a lot to an exhibition, if adequately designed and kept in balance with the other content elements and the interior design.

To avoid distracting and overwhelming the visitors, it is often best to design more subtle exhibition soundscapes with very targeted sounds for different areas of each exhibition room. Minimalist elements used in this way combine to create the global soundscape of the exhibition. If designed like this, a museum soundscape can feel more like a journey that dynamically changes according to the visitor’s path through the exhibition, earlier sounds becoming inaudible as the visitor proceeds through the exhibition room. All the parts should work together, each element adding a unique aspect to the soundscape. I see it a bit like a musical composition that is built from different instruments to create the piece as a whole. Depending on the position in the space, some “instruments” are audible, and some are not. If designed well, such a soundscape can work as a guiding thread through an exhibition, complementing the other exhibits and adding emotion and meaning while remaining invisible.

Since sound is such an immediate medium, it is a significant factor in how an exhibition feels to an audience. It is much simpler to create the intended audience experience if an exhibit is designed with sound considered from the beginning, rather than being to “tacked on” at the very end.

I think that there is a vast potential for using sound in exhibitions in new and exciting ways, waiting to be explored.

Q&A: Museum Sound Design II

Questions: Alice Millar, University of Oxford

Answers: David Kamp, Studiokamp

I am particularly interested in your design for the Smithsonian’s Wendell Philipps exhibition. Could you tell me about how you curated the soundscape: how do you choose which sounds you want to include and exclude?

The design of my soundscape for the Wendell Philipps exhibition at the Smithsonian was based mostly on wind sounds recorded in the Yemeni desert. There were many reasons for using these sounds as the backbone of the soundscape:

1) Those sounds immediately give a sense of place and transport the visitor to a new environment while being rather neutral, subtle and not overly distracting or fatiguing, even when played for longer periods of time.

2) The wind sometimes carries far away sounds to the listeners ears, and the source of the sound is not immediately obvious. This phenomenon was key to my concept of the soundscape. It allowed me to blend different sounds, distant music fractions and voices which slowly emerged from the whistling wind as if carried from far away to the listeners ears, only to slowly disappear into the far distance again.

3) In desert regions – and likely as well during Philipp’s expedition in Yemen – the sound of wind is a permanent companion of the exhibition, so making that a key component of the soundscape made sense to me and the team at the Smithsonian.

Many of the other sounds used for this exhibition soundscape are processed sounds from tape recordings made during Wendell’s Yemen exhibitions. In addition to these sounds I created short snippets of various historical recordings of traditional music of the region from the Smithsonian’s “Folkways” archive of sound recordings.

These fragments, mostly music and voices, were often used like a sound texture and selected based on their sonic qualities instead of their semantic content. Voice recordings were sometimes muffled and processed so that they sound further away. This helped to create a better blend with the wind sounds and stopped them from becoming a focus point and potential distraction. The goal of the soundscape here was not to convey a specific narrative or deliver “information” to the audience, rather to set the mood for the space, and let the texts, images and objects in the exhibition space be the more “conscious” element of the overall experience.

How do you view your role as a sound designer? Do you see yourself as someone that collects, edits together produced pre-existing sounds in a translatory process or is sound design more of a construction?

It can be both and entirely depends on the specific project and exhibition and its goals.

I am a trained composer (Degree in Electronic Composition ICEM, Folkwang University of Arts), so that background helps me with creating sonically coherent soundscapes from different materials, whether those sonic building blocks are very concrete sounds, more abstract and designed, or even synthesized from scratch.

Could you tell me about how you feel that sound is altered to engage children for the work you did with Tate Kids?

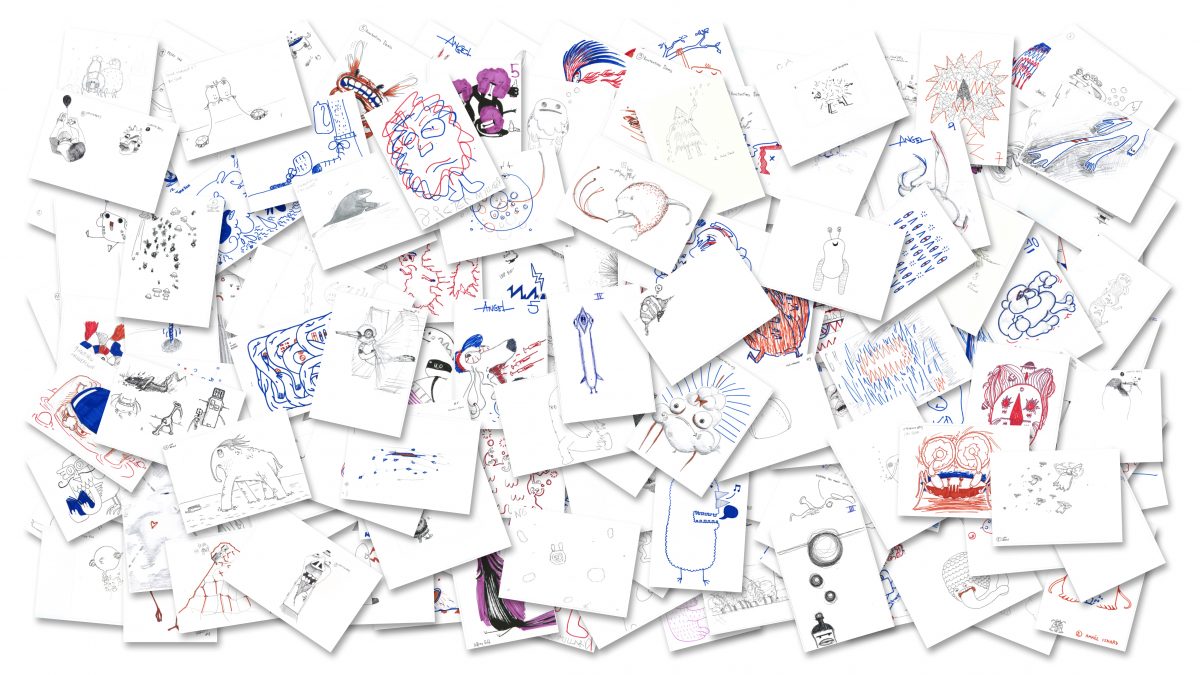

What I did with Tate Kids was a variant of my “draw sounds” project. I came up with this concept of drawing “creatures” based on sounds many years ago and went through a few iterations of the concept from small group workshops to having bigger conference audiences draw my sounds. The common thread is that I designed sounds of “Imaginary” creatures and habitats and people would draw what they thought those creatures or their environments looked like. For Tate Kids I designed a few unique sounds geared towards kids which they could draw. These were based on my experience of what kids in these particular age groups seemed to enjoy most in my previous workshops.

I am not sure if there is a specific way that sounds are “altered” to engage children, at least in my work I think I’d try to avoid that – except for staying away from anything overly harsh or frightening because kids often experience sounds differently and sometimes more intensely than older age groups. I also feel like there are certain cliches of “playful” children sounds that I try to avoid since kids are bombarded with them constantly in apps, advertising, and television programs.

Do you feel inspired or affected by the space that the soundscape will be displayed in? Do you fit the sound to the space, or does the sound fill a given area?

This depends on the concept for the exhibition content and the space it is presented in.

I’ve used very located sounds, where the audience would follow a “sound path” with clearly defined stages and sections, and I’ve made works in very reverberant rooms where the soundscape filled the entire room. Both can work well depending on what the intent of the exhibition is and what type of sound material is used for the museum soundscape. Some things are obviously problematic in large reverberant rooms, anything percussive and rhythmically complex for example.

Are sound installations intended to be interactive? Do the sounds that visitors make add to the art and alter it, or does sound art perform more like visual art (separated from the visitor by barriers, alarms, etc.)?

It can be both and both are valid. I like the idea of interactivity in theory, but in my experience interactivity can easily become a chore which the user has to do to cause a sound reaction. This can quickly become predictable and boring, or if the interactivity is too complex the sonic “response” of the installation can feel random and disconnected from the user’s action.

There are certainly a few very successful interactive sound installations, where interactivity is a key element that is more than a “gimmick” and the audience gets a sense of being part of the installation in a way that they wouldn’t in a non-interactive sound installation.

Do you view sound art and sound in museums as at odds with visual displays, or are they complementary?

In my work with museums I try to avoid redundancy of visual display and audio content. A simple example: if a visitor is likely to stand in front of a text-heavy exhibit, the audio should dial back to setting the mood, rather than conveying (spoken) information. That way the two elements can complement each other.

This also works the other way around, when an exhibition room is not filled with content and narrative the soundscape can take this role, the classic example being an audio guide. Even though I have worked with techniques of using GPS or Bluetooth beacons to create localised sound for each visitor and tying the sound experience to specific areas of the exhibition room, I generally prefer a shared “soundscape” for the audience, avoiding headphones as a requirement to experience the exhibition. An exception was an AR project for Naturkunde Museum Berlin, done in collaboration with the team at neu.io and “mediasphere for nature”, where geolocated binaural 3D-audio played from a mobile device was at the core of the experience. Each visitor was guided through the thousands of birds on display in the “Vogelsaal” by following the localised calls of specific birds, which became louder and clearer the closer each visitor got to the species they heard. This was a good example of visual displays and sound really complementing each other.

How has the fact that museums are increasingly moving their collections online affect sound art and sound installations? For example, you have several of your pieces available for listening on your website, so how do you feel that the audience changes whether the soundscape is heard online or in a traditional museum setting?

While I like working with sound in a physical space, and there are certain sound art works/installations with a decidedly physical sound source that will only work well in those spaces, there are upsides to going online. In general, I think collections going online is a good thing, since the art becomes more accessible to people who can’t physically visit the museum.

For example, my recent work with the Bauhaus Museum “Bauhaus Sounds” (a museum soundscape based on my recordings of Bauhaus objects and architecture ) was conceived conceived to be independent of the physical space for playback from the beginning. While all sound recordings that formed the material of the soundscape (Building materials, acoustics, design objects) are 100% physical and made from and in the Bauhaus premises in Dessau, the soundscape itself is available in the Bauhaus app and can be listened to anywhere in the world.

That way it serves as a backdrop for the visitors of the new Bauhaus Museum in Dessau, but is not limited to the Bauhaus building itself. People can listen to it while in transit between the Museum and nearby Bauhaus “Meisterhäuser” and other Bauhaus locations, which helps connect the experience of visiting Bauhaus Dessau sonically.

I believe it is equally possible to design a sound art piece or a soundscape for a physical space or for online audiences and adapt it for both accordingly. With new technical possibilities for real time sound playback we are getting closer to fully representing a 3D soundscape via headphones and make it feel as immersive as a physical space. The advantage of online is of course a bigger reach and audience, while a well designed physical space often creates a more direct experience. A physical exhibition gives us precise control of the loudspeakers used and the absolute sound level. Further, we can be sure of a certain quality of sound projection, whereas online visitors listen with all sort of devices, headphones and speakers, in a wide range of listening environments.

I think the boundaries between virtual and physical spaces will become less and less relevant in the near future and museum soundscapes should be conceived and designed with both in mind, taking advantage of the strengths of each format.

Explore Studiokamp’s projects related to museum sound design, sound art and spatialized sound